USCHO Fan Forum

-

The USCHO Fan Forum has migrated to a new plaform, xenForo. Most of the function of the forum should work in familiar ways. Please note that you can switch between light and dark modes by clicking on the gear icon in the upper right of the main menu bar. We are hoping that this new platform will prove to be faster and more reliable. Please feel free to explore its features.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

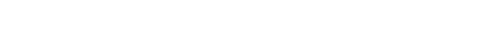

Philosophy 1: Wittgenstein was a beery swine who was just as sloshed as Schlegel

- Thread starter Kepler

- Start date

MissThundercat

Are the cis okay?

I went back and picked up The Plague and The Fall by Camus; I find his works comforting and full of what I call "healthy positive energy."

And for turning 42 on September 20, "the only thing left to hope is there are spectators and there will be howls of execration on the day of my execution."

And for turning 42 on September 20, "the only thing left to hope is there are spectators and there will be howls of execration on the day of my execution."

Kepler

Si certus es dubita

So, there are some questions I have run into in philosophy which fall into the "if it wasn't for my horse" category. They are innocuous on the surface but once they are ingested they begin to work on you and work on you and pretty sure you're down/up/whatever spatial metaphor you like into cognitive territory where you recognize that our concepts are insufficient -- that the world is not small enough to fit inside our head.

Here is my most recent one: does the past still exist?

I dismissed that question for years until at some point it hooked itself onto some barbs in my thought structure and now it's kudzu, ruining the whole garden. It's such a stupidly beautiful example of something so in front of your nose you can go your life without seeing it. it's infuriating like all good metaphysics in that it recedes when you apporach, and then coaxes you when you give up and say "fine, stay over there."

It's an idea cock tease.

Here is my most recent one: does the past still exist?

I dismissed that question for years until at some point it hooked itself onto some barbs in my thought structure and now it's kudzu, ruining the whole garden. It's such a stupidly beautiful example of something so in front of your nose you can go your life without seeing it. it's infuriating like all good metaphysics in that it recedes when you apporach, and then coaxes you when you give up and say "fine, stay over there."

It's an idea cock tease.

Kepler

Si certus es dubita

In some other reading I came upon this guy.

He's genuinely fascinating. He was a significant theological scholar who found his reasons for opposing the European practices of forced conversion, as well as enslavement and dispossession of Native Americans in his own philosophy which is still grounded in his idea of Christian ethics. The other text I am reading was talking about Medieval ideas of hierarchy, specifically the idea that just authority proceeds downwards from a One to a Many. The model, obviously, is God, and is then extended to the family, the state, etc by analogy.

This was a popular but by no means universally accepted theory in Christian theology. There was a competing theory, conciliarism, which will knock your socks off because it boils down to the legitimatization of authority being consent of the governed. And you thought Locke and Jefferson were being original, and here it is, 200 years before them with some monks playing shuttlecock with Angels on the head of a pin. Frank the Winner comes along, lifts that like a lance, and drives it right through the heart of colonialism, arguing that Native Americans (1) are human, given they can interbreed with Europeans, (2) are rational, given that they have customs, laws, language and government, and therefore (3) they cannot be deprived of their will, freedom, or possessions simply on the grounds of being "sinners," because as rational men (sorry, ladies) they have agency and natural dignity. The one exception is when they try to commit human sacrifices, as those in turn are violations of another's dignity and can be rightly stopped. (Frank does appear to say you can actually genocide tribes who employ human sacrifice, so I guess the principle of proportionality is a bit rusty in the early 16th century, but, I mean, come on, it didn't stop Truman from flattening Hiroshima.)

Anyway, from my very brief reading I think this guy goes into the pantheon of Good Folks with the Fancy Words, which is not all that large.

He's genuinely fascinating. He was a significant theological scholar who found his reasons for opposing the European practices of forced conversion, as well as enslavement and dispossession of Native Americans in his own philosophy which is still grounded in his idea of Christian ethics. The other text I am reading was talking about Medieval ideas of hierarchy, specifically the idea that just authority proceeds downwards from a One to a Many. The model, obviously, is God, and is then extended to the family, the state, etc by analogy.

This was a popular but by no means universally accepted theory in Christian theology. There was a competing theory, conciliarism, which will knock your socks off because it boils down to the legitimatization of authority being consent of the governed. And you thought Locke and Jefferson were being original, and here it is, 200 years before them with some monks playing shuttlecock with Angels on the head of a pin. Frank the Winner comes along, lifts that like a lance, and drives it right through the heart of colonialism, arguing that Native Americans (1) are human, given they can interbreed with Europeans, (2) are rational, given that they have customs, laws, language and government, and therefore (3) they cannot be deprived of their will, freedom, or possessions simply on the grounds of being "sinners," because as rational men (sorry, ladies) they have agency and natural dignity. The one exception is when they try to commit human sacrifices, as those in turn are violations of another's dignity and can be rightly stopped. (Frank does appear to say you can actually genocide tribes who employ human sacrifice, so I guess the principle of proportionality is a bit rusty in the early 16th century, but, I mean, come on, it didn't stop Truman from flattening Hiroshima.)

Anyway, from my very brief reading I think this guy goes into the pantheon of Good Folks with the Fancy Words, which is not all that large.

Last edited:

MissThundercat

Are the cis okay?

I moved into Foucault and I'm getting it. I get that fascism and authoritarianism are maintained by the individual because we love having power.

Kepler

Si certus es dubita

Kepler

Si certus es dubita

This is the finest synopsis of Schopenhauer's The World as Will and Representation I have ever read:

What is the nature of reality? The entire world is just an idea. That’s it. Kant was so close, but Berkeley f-cking nailed it - the entire world is one biga-ss idea. There are two parts to this idea: object and subject, which sound more complicated than they are. The ‘object’ is just all the things that anyone perceives; it’s the entire world as we know it. Except that you can’t have a perception without someone perceiving it, and that is the subject, the 'haver’ of the idea. It’s like when a bro sees something; his perception of seeing is the object, and the bro himself is the subject, except these are inseparable. You can’t have one without the other - there’s no thought without a thinker, and you’re not thinking if you don’t have thoughts. It really is all just one big f-cking Idea. Any attempt to separate 'object’ and 'subject’ into truly different things, rather than parts of the same Idea, is doomed to failure, just like any attempt to separate ‘sight’ from ‘the bro who sees’ makes no sense.

But that’s not enough. Kant said we want to know ultimate reality behind the Idea, and he was f-cking right - we aren’t happy being told that it lies beyond our grasp. F-ck that noise - I want to know what my ideas mean, what they say, whether there is any substance behind them, and if that yearning is wrong then I don’t want to be right. Of course, Kant was right that we can never grasp ultimate reality from the outside looking in, which is exactly what everyone before me has tried. But where they all f-cked up, and what makes me awesome, is that they all imagined themselves as winged cherubs, looking down on the world without being a part of it. But we are in the world as much as anything else; our bodies are objects just like the chair I’m sitting in. What sets my hand apart from the pen it holds? What if my body were just the object I’m closest to, and I had no more control over it than your body, which is also an object to me?

Answer: Pure. Motherf-cking. Will. My willpower is the only thing that sets my body apart from any other object; the will manifests itself in the movement of my body. Emotions? Just violent movements of the will, as these too cause my body to react, whether my heart races or my breathing slows or, uh, you know… boners. Only the will allows us to take the body beyond an object of perception. The Will manifests itself into individuals, and these perceive and react, but they all have the same ability to perceive, and that ability is the subject itself.

What sets man apart is his ability to reason, to replace perception with abstract ideas - not only do we perceive individual things, we can categorize them and reason about them. Picture a triangle - got it? Good. No lower animal could complete such an exercise, but we can understand the idea of all triangles, or all numbers, or all cats; behind every perception is an abstract idea. And the idea behind every abstract idea, the highest idea, is pure unadulterated Idea - the Idea of being object for the subject, the Idea of being an Idea. This highest Idea is the ultimate reality - Idea itself. When we strip away even the notions of object and subject, only one thing remains that is neither - the goddamn Will, which is the thing-in-itself that Kant thought we couldn’t know. Well there it is, b-tches.

The Will is conscious, and is consciousness itself. Individual wills live and die, but they always maintain the Will itself. The Will exists now, in every moment, never in the past or the future. We have free Will indeed, for no reason or necessity or determination can constrain the Will. If we would participate in the thing-in-itself fully, we ought to live only in the present, with no regard for tomorrow or yesterday! By embracing the will, we need not fear death, for death is an illusion for individuals, and the Will we embrace is eternal.

Last edited:

MissThundercat

Are the cis okay?

Kep, I'm attempting to read Nietzche. Surprisingly easy to read, unlike Hegel.

Kepler

Si certus es dubita

Kep, I'm attempting to read Nietzche. Surprisingly easy to read, unlike Hegel.

He's a lot of fun.

Kepler

Si certus es dubita

Kep, I'm attempting to read Nietzche. Surprisingly easy to read, unlike Hegel.

I am rereading On the Genealogy of Morals after not looking at it for 10 years, and suddenly it's brilliant and clear.

MissThundercat

Are the cis okay?

I am rereading On the Genealogy of Morals after not looking at it for 10 years, and suddenly it's brilliant and clear.

I'm working through Zarathustra myself.

I don't know Spinoza, but it appears he is very relevant to today's political environment. This excerpt from Ian Buruma's Spinoza: Freedom's Messiah will prompt me to do some reading:

Spinoza was convinced that all people, regardless of their religious or cultural background, were imbued with the capacity to reason and that we should seek the truth about ourselves and the world we live in. He insisted that our rational faculties could provide us with not only more precise knowledge but also with a path toward a happier life and better politics. In an essay called “On the Correction of the Understanding,” he wrote, “True philosophy is the discovery of the ‘true good,’ and without knowledge of the true good human happiness is impossible.” That true good, in Spinoza’s view, can only be found through reason and not through religion, tribal feelings or authoritarianism.

Unlike Thomas Hobbes, who believed that only an absolute monarch could keep man’s violent impulses in check, Spinoza was an early proponent of a democratic ideal and representative government. But a free republic could only survive under a government of reasonable men who knew how to cope with conflicting interests rationally. As Spinoza put it, perhaps a little too optimistically, in his “Theological-Political Treatise”: “To look out for their own interests and retain their sovereignty, it is incumbent on them most of all to consult the common good and to direct everything according to the dictate of reason.”

Spinoza was convinced that all people, regardless of their religious or cultural background, were imbued with the capacity to reason and that we should seek the truth about ourselves and the world we live in. He insisted that our rational faculties could provide us with not only more precise knowledge but also with a path toward a happier life and better politics. In an essay called “On the Correction of the Understanding,” he wrote, “True philosophy is the discovery of the ‘true good,’ and without knowledge of the true good human happiness is impossible.” That true good, in Spinoza’s view, can only be found through reason and not through religion, tribal feelings or authoritarianism.

Unlike Thomas Hobbes, who believed that only an absolute monarch could keep man’s violent impulses in check, Spinoza was an early proponent of a democratic ideal and representative government. But a free republic could only survive under a government of reasonable men who knew how to cope with conflicting interests rationally. As Spinoza put it, perhaps a little too optimistically, in his “Theological-Political Treatise”: “To look out for their own interests and retain their sovereignty, it is incumbent on them most of all to consult the common good and to direct everything according to the dictate of reason.”

Last edited:

Kepler

Si certus es dubita

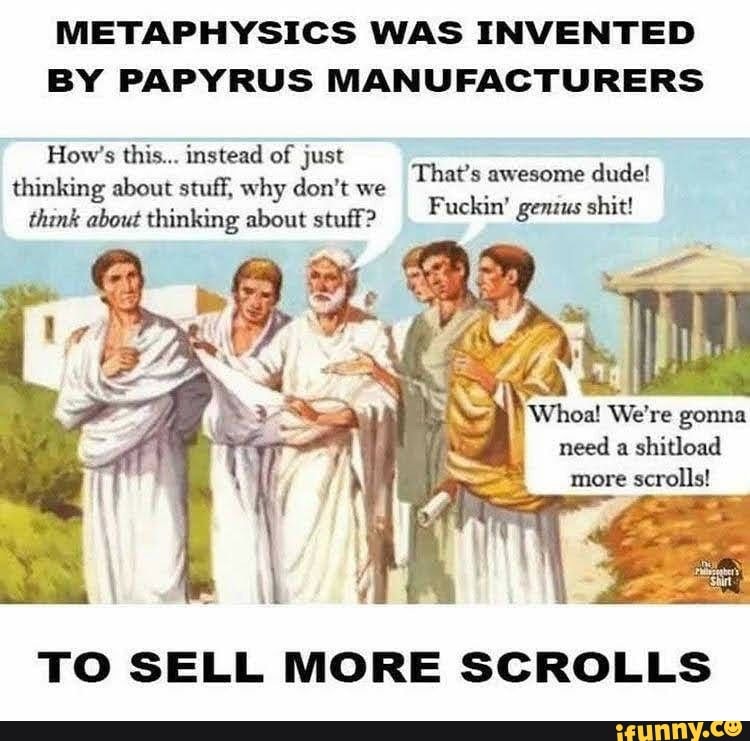

That is interesting. I know nothing of Spinoza's political or ethical theories. His greatest book, Ethics, is ironically about metaphysics, not ethics.

The conception "without knowledge of the true good human happiness is impossible" is very Greek. Plato has Socrates say that all wrong action stems from ignorance, and Christianity cribbed that as the Neoplatonic idea that evil is distance from truth (God).

There is a long tradition in philosophy that if we could just know the truth we would no longer commit bad acts, because the end of human beings is what they perceive as their happiness -- therefore, if we knew truth we would pursue it in our own self-interest.

The conception "without knowledge of the true good human happiness is impossible" is very Greek. Plato has Socrates say that all wrong action stems from ignorance, and Christianity cribbed that as the Neoplatonic idea that evil is distance from truth (God).

There is a long tradition in philosophy that if we could just know the truth we would no longer commit bad acts, because the end of human beings is what they perceive as their happiness -- therefore, if we knew truth we would pursue it in our own self-interest.