USCHO Fan Forum

-

The USCHO Fan Forum has migrated to a new plaform, xenForo. Most of the function of the forum should work in familiar ways. Please note that you can switch between light and dark modes by clicking on the gear icon in the upper right of the main menu bar. We are hoping that this new platform will prove to be faster and more reliable. Please feel free to explore its features.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Science: Everything explained by PV=nRT, F=ma=Gm(1)•m(2)/r^2

- Thread starter joecct

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Kepler

Si certus es dubita

Neuroscience: it is possible for stupid people to learn mechanisms to recognize and compensate for their limitations. They do not have to personify Dunning-Kruger.

Either teach this in every school or take away their right to vote.

Either teach this in every school or take away their right to vote.

Kepler

Si certus es dubita

Obvious.

The researchers found that daily smartphone checking predicted higher levels of daily cognitive failures even after controlling for age, sex, monthly household income, subjective socioeconomic status, daily stressor exposure, daily positive affect, and daily negative affect.

“We found that on days where individuals engaged in more smartphone checking, they were more likely to experience cognitive failures, when compared with days when they engaged in less smartphone checking,” Hartanto told PsyPost. “This suggests that smartphone excessive smartphone checking is a distracting behaviour that increases cognitive load and thus cognitive failures.”

Kepler

Si certus es dubita

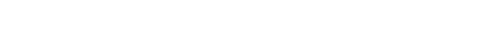

Scientists have a dark sense of humor.

Kepler

Si certus es dubita

I read a great proposition that modern science began in 1277. Pierre Dunhem, a medievalist about a hundred year ago, hypothesizes that The Condemnations at the University of Paris made philosophers paranoid about suggesting god has any limitations on action except logical contradiction. Ironically this increased the amount of contingency in accounting for natural observations. You could no longer simply deduce the order of the world from rational principles because then you were limiting god. But that meant philosophers were more free to start to directly observe and collect empirical evidence because there were an infinite number of ways god may have organized the universe.

This had the effect of weakening and eventually Aristotle's dogma about final cause, since there was no "purpose" to argue creation, from god's will. The dismissal of final cause -- teleology -- as false analogy is the cornerstone of modern natural science and opened our minds to the complex, probabilistic understanding of reality that allows us to land rockets on comets.

This had the effect of weakening and eventually Aristotle's dogma about final cause, since there was no "purpose" to argue creation, from god's will. The dismissal of final cause -- teleology -- as false analogy is the cornerstone of modern natural science and opened our minds to the complex, probabilistic understanding of reality that allows us to land rockets on comets.

MichVandal

Well-known member

I read a great proposition that modern science began in 1277. Pierre Dunhem, a medievalist about a hundred year ago, hypothesizes that The Condemnations at the University of Paris made philosophers paranoid about suggesting god has any limitations on action except logical contradiction. Ironically this increased the amount of contingency in accounting for natural observations. You could no longer simply deduce the order of the world from rational principles because then you were limiting god. But that meant philosophers were more free to start to directly observe and collect empirical evidence because there were an infinite number of ways god may have organized the universe.

This had the effect of weakening and eventually Aristotle's dogma about final cause, since there was no "purpose" to argue creation, from god's will. The dismissal of final cause -- teleology -- as false analogy is the cornerstone of modern natural science and opened our minds to the complex, probabilistic understanding of reality that allows us to land rockets on comets.

Only if you are looking for a connection with "modern" science and engineering and it HAS to be European.

But IMHO, that totally and utterly dismisses the work people we label "ancient". They had to have a VERY solid understanding of observational science to build the structures they did- from the middle east to the Americas. And these go back many thousands of years. Heck, I think it can be argued that early science was when someone figured out that a slow jog that a human was capable of doing would kill a deer for running itself out of breath. Which would date back to when humans were hunter gatherers.

Sorry, but I dismiss any theory that discounts how smart and observational people have been forever. Humans have ALWAYS been smart and observational. "Technology" limited what could be recorded and passed on.

Kepler

Si certus es dubita

Sorry, but I dismiss any theory that discounts how smart and observational people have been forever. Humans have ALWAYS been smart and observational. "Technology" limited what could be recorded and passed on.

I don't think I have done a good job explaining the argument. It is not that intelligence and empiricism were born in the 13th century, or in the West. Obviously neither of those things has a birth, they are as old as humanity.

The argument is that Aristotelianism, which dominated European and Anatolian and Middle Eastern and North African intellectual culture from 300 BC through 1300 AD, had a fatal flaw which had to be overcome before science could progress. It's ironic because Aristotle himself, a physician and naturalist, would almost certainly have wholly rejected the slavish reification of it. That flaw was the conceit that everything in the universe has four causes: efficient, formal, material, and final. The first three map, roughly, to the reality of the natural world (etiology, morphology, chemistry), and they are quite useful.

The final cause is a superstition held over from the personification of nature of primitive cultures. It posited there was a thing that dictated natural existence intentionally, the way a carpenter dictated the existence of a chair. So, an acorn is the final cause of a tree: its purpose is to create more trees. Aristotelianism dictated every aspect of nature had a purpose, and therefore that you could reason your way to the purpose. The primary work of the natural philosopher was in the mind -- to figure out the reasonable chain that led from creator to created.

12th and 13th century philosophers reinforced the notion, ironically in the service of harmonizing the divine and the natural. Aquinas believed that god is free but that freedom is defined by necessity. God's freedom is not arbitrary or contingent, it follows from the nature of god and the world. Everything happens for a reason. Aquinas did not suggest this limited god, but merely said that necessity as perceived by limited beings like humans was god's will. And again, that leads you back into the Aristotelian box. No need to touch grass to understand the existence of grass. One only needs to follow the chain: god created animals, some animals graze on grass, ergo grass exists to feed those animals.

The authorities in Paris perceived these notions as a threat since they appeared to bind god, so they were declared anathema. Natural philosophers could take a hint -- they didn't wind to wind up on the business end of a stake -- so they branched out their theorizing in other directions from the strict Aristotelianism of the 13th century and began to concoct all sorts of interesting ways of viewing the world as the result of god doing whatever he wanted when he wanted. This opened up the possibility of, literally, possibility: other possible ways of being that just didn't happen to come up on the Magic 8 Ball. And that perhaps did not invent but did strongly support a strand of human inquiry which otherwise would have been suppressed due to dogma.

It's a great irony that an attempt to roll back metaphysics to an authoritative formula resulted in the intellectual movement that eventually destroyed not just the formula but the authority, and created modernity.

Now you may well ask if India and China had anything like a similar development. I'd love to know. I know very little about China and all I know of India is they were doing the mathematics it took Europeans until 1900 to understand in, literally, the 11th century.

Last edited:

MichVandal

Well-known member

I don't think I have done a good job explaining the argument. It is not that intelligence and empiricism were born in the 13th century, or in the West. Obviously neither of those things has a birth, they are as old as humanity.

The argument is that Aristotelianism, which dominated European and Anatolian and Middle Eastern and North African intellectual culture from 300 BC through 1300 AD, had a fatal flaw which had to be overcome before science could progress.....

(cut)

Now you may well ask if India and China had anything like a similar development. I'd love to know. I know very little about China and all I know of India is they were doing the mathematics it took Europeans until 1900 to understand in, literally, the 11th century.

There's a whole lot more to the world than that- like the entire Americas. And to assume that every human in all of history carried the same flaw is a pretty flawed assumption. Let alone interpreting the flaw as something that prevented science to progress. Science includes astronomy, which is well known to be very accurately mapped by many ancient groups. Science includes architecture- so yea. Science includes farming progress- which had that not happened, humans would still be hunter/gatherers. Science includes naval architecture- and there were plenty of sail boat designs well before 300 BC. I can go on if you want.

Sorry, but to say that one instance changed everything diminishes all of what humans did prior to that which required science thinking to accomplish that feat. Humans learn by observation, they come up with a theory, and if the theory fits the observation, great, if not, they think it though and work it out. Fire, Water, earth, air as the 4 elements fit good enough until someone observed that it didn't and dug deeper.

If it's not clear, there's one show that drives me utterly crazy- ancient aliens. All it really does is pretend that our old old old parents were not clever enough to have done all of the things we dug up and aliens had to have done it for them. What utter crap. Scientific kind of observations have been happening for many, many, many millennia. And just looking into what is being found, you can see real development in real science.

Last edited:

Kepler

Si certus es dubita

We are talking at cross purposes. Nothing you are saying in any way contradicts an interesting perspective I had not thought about before that I wished to share, and that has depths I won't fully appreciate without a lot more thought.

As far as "science" is concerned, the argument has to do specifically with modern science, a rigorous application of the scientific method to a mountain of intentionally gathered, methodically recorded and analyzed observational data. The are several comparable projects before the modern period: Sumerian astronomical observations, Chinese irrigation planning, and Egyptian flood records are obvious examples. Again, nothing in the argument speaks to this. This isn't that fight.

As far as "science" is concerned, the argument has to do specifically with modern science, a rigorous application of the scientific method to a mountain of intentionally gathered, methodically recorded and analyzed observational data. The are several comparable projects before the modern period: Sumerian astronomical observations, Chinese irrigation planning, and Egyptian flood records are obvious examples. Again, nothing in the argument speaks to this. This isn't that fight.

Last edited:

MichVandal

Well-known member

We are talking at cross purposes. Nothing you are saying in any way contradicts an interesting perspective I had not thought about before that I wished to share, and that has depths I won't fully appreciate without a lot more thought.

As far as "science" is concerned, the argument has to do specifically with modern science, a rigorous application of the scientific method to a mountain of intentionally gathered, methodically recorded and analyzed observational data. The are several comparable projects before the modern period: Sumerian astronomical observations, Chinese irrigation planning, and Egyptian flood records are obvious examples. Again, nothing in the argument speaks to this. This isn't that fight.

I'm not even reading the article, as I really object that we have to disseminate periods of science like that . Deciding what "modern" means is rather arbitrary and really just tries to reduce our parents to people who could not think as well as we think we do.

It took that same observation and application of knowledge to make the statues at Easter Island. Or the various observatories around the world at various periods (a famous one being Stonehenge). Or any massive building project- like in central America - right angles being that precise over a long distance requires significant observation and conclusions. And the long term development of corn here in the Americas.

Everything that is defined as "modern science" has been done for millennia. Just because it wasn't written down the same does not mean it wasn't done. Or that it uses the same math that we have all decided is super important.

Again, that kind of thinking just results in more current people thinking that ancient people were not capable of building the pyramids or develop farming or observe the stars. I really hate that thinking.

I am ok with noting massive changes in science- like when calculus was really invented. Where the change made progress a whole lot easier as it gave us much better models to work with.

MissThundercat

Are the cis okay?

Nature is super neat.

https://www.livescience.com/2-orcas...-418E-9BED-59BBFD377DE2&utm_source=SmartBrief

https://www.livescience.com/2-orcas...-418E-9BED-59BBFD377DE2&utm_source=SmartBrief

Kepler

Si certus es dubita

FRBs as merging neutron stars.

tldr: neutron stars collide --> become black hole --> powerful magnetic field shuts off --> generates an enormous radio burst --> voila

tldr: neutron stars collide --> become black hole --> powerful magnetic field shuts off --> generates an enormous radio burst --> voila

Kepler

Si certus es dubita

Kepler

Si certus es dubita

Keep, I seem to recall you saying that you took your username from the name of your cat. If so, was the cat named after the 17th century German astronomer/philosopher?

Yes. When he would play with one toy, a ball on a string, when the ball was moving in a circle he would always whack it so it turned into an ellipse.

He was my first kitty and I miss him very much.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.